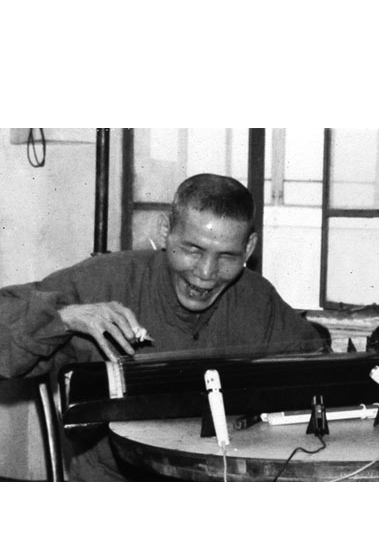

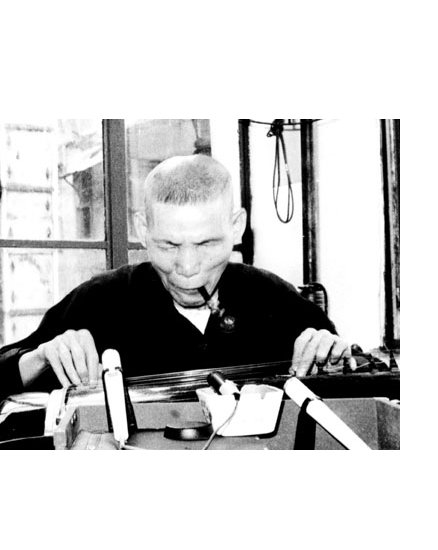

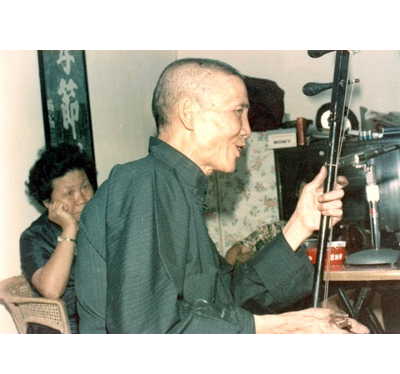

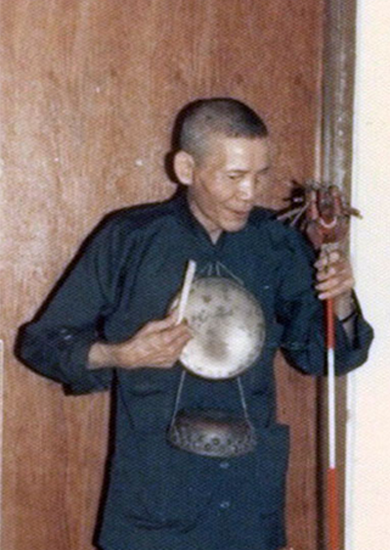

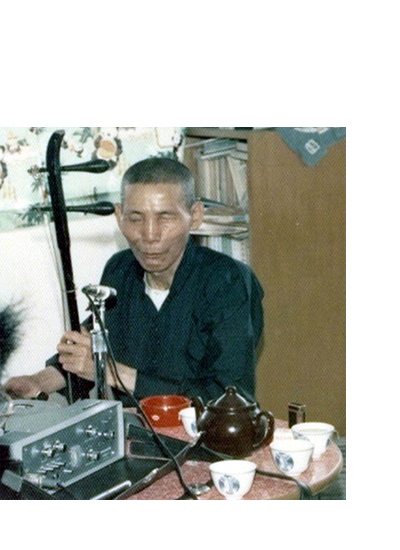

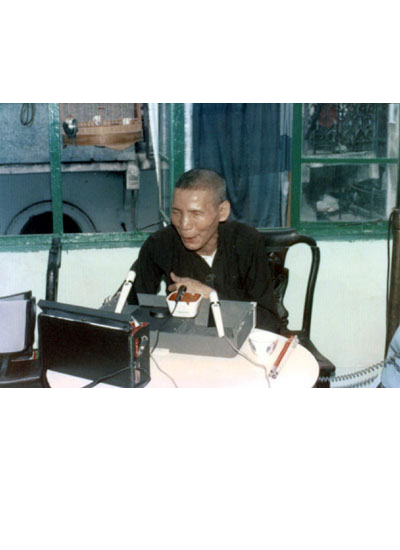

One night in 1974 (may also be 1975), Ho’s driver, Bro. Cheung, finally put Douwun in touch with his boss. After the union, Douwun frequented Ho’s mansion again. Ho, like before, was very magnanimous to him; he received him courteously, and never bothered with what and how long he sang. Even though Douwun became frail and lacked the strength to sing long, the Ho family still paid for his performance.

The Ho family gave Douwun absolute respect. They let him perform in their living room and ordered the driver to take him from the Edinburgh Place in Central to their mansion. Douwun was immensely moved by what they did.

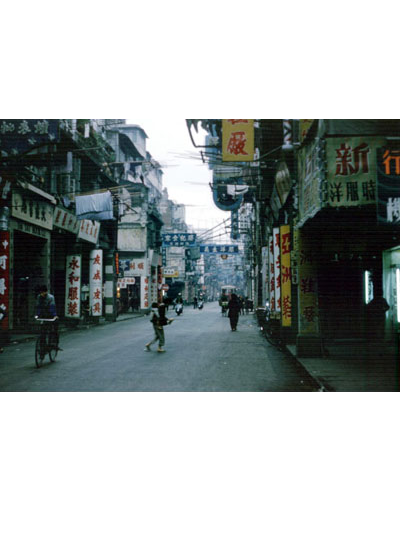

In not a few occasions Douwun expressed his appreciation: “the Ho family in Hong Kong was so much different from the wealthy in Guangzhou!”

They were very munificent, very munificent.

The entire family, old and young,

was great-hearted and decent.

He, noble and truthful, deserved

to be a gentleman of wealth!

I still remember when I was young…

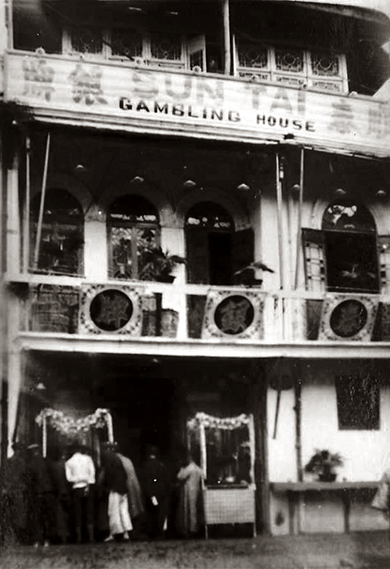

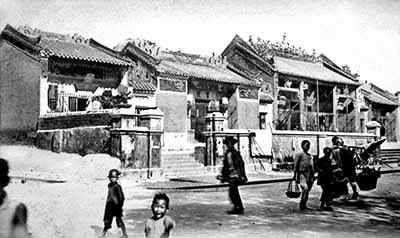

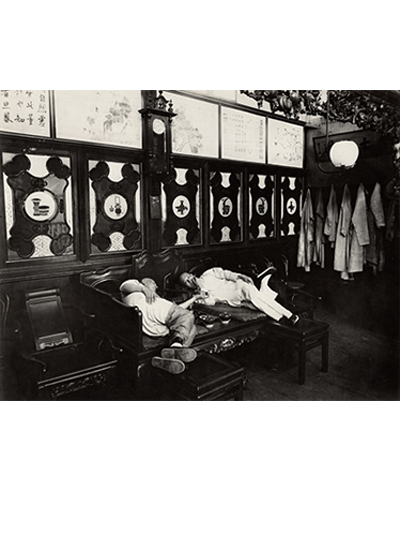

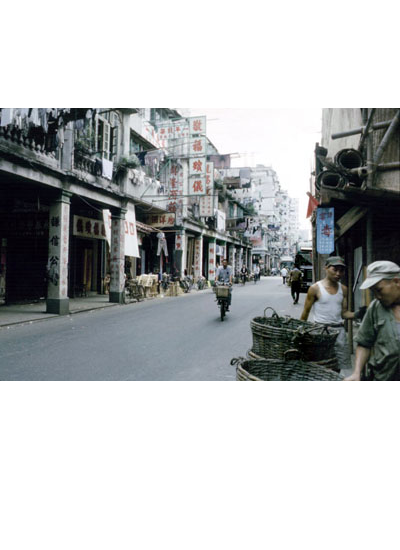

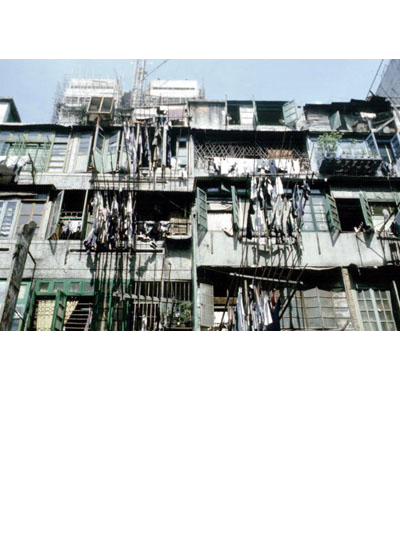

(Speech) Ah! The gentleman Ho Iu Kwong, and in fact his entire family, was incredibly nice. So noble and humble and courteous! They deserved to be rich. Why? When I was young, I remember, I followed my master to Guangzhou. Where do you think I went? It’s quite laughable, quite laughable indeed, thinking back on the day. The place was called Tian Xin, you know, because the family was surnamed Tian Xin, and the man’s called Tian Xin Yang. So they sent for my master, and since I was his new pupil I had to follow him. When we got there — what do you think was the foodstuff? They ate well, of course, but we were ill-treated. The teacup, you know, we had to use those called the sunflower teacup, that is, those the servants used. So different from what they’d been using — I had a peek to their table as I could see better in youth. You get the idea how mean they were. The teacup was for maids, also the dish-washing maids. Our food, too, was different from theirs. We were not even given a proper chair, you know, but a bench that’s for the maids to sit in kitchen. That’s what they gave us for resting. You see, poles apart from the temperament of the Ho family. Poles apart!

(Lyrics) Thinking back to the past,

it’s interesting to notice

the very different characters

of people in the world at large.

To class them together,

it’s simply two worlds,

like heaven and hell, no blather.